A new light on the Transatlantic slave trade in Enslaved

Samuel L. Jackson and LaTanya Jackson’s documentary series Enslaved sheds light on 400 years of crime and horror

The documentary series Enslaved: The Lost History of the Transatlantic Slave Trade is a labour of love from husband-and-wife co-producer team Samuel L. Jackson and LaTanya Richardson Jackson. They've channelled a lifelong shared passion for civil rights into the 6-episode series and in doing so, re-framed many historical events from the points of view of those Africans whose lives and futures were stolen for financial gain.

In the early days of production on Enslaved, Samuel and LaTanya’s partnership led to a flurry of notes between New York and LA, as LaTanya was playing Calpurnia in To Kill A Mockingbird on Broadway until November 2019. It’s Samuel we see on screen as he traces his roots to Ghana, and travels around the world on the trail of history with author/broadcaster Afua Hirsch and Emmy Award-winning investigative journalist Simcha Jacobovici. But LaTanya’s voice comes through clearly in Enslaved’s portrayal of the Transatlantic slave trade’s kidnapping and sale of African people as a crime.

Samuel and LaTanya spoke to us about their exploration of the trade and its victims, and more…

Coming to grips with Enslavement

LaTanya and Samuel come from somewhat different backgrounds, and it impacted how they grew up understanding the history of slavery in the United States. It’s also a shocking reminder that the Transatlantic Slave Trade is by no means ancient history. The last known survivor of the slave ships, Matilda McCrear, a Yoruba child, was taken from Africa at the age of 2 aboard the slave ship Clotilda, and died in Selma, Alabama, in January 1940, at the age 83.

The impact of vicious racism lingered in Samuel’s own life in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He was born in 1948, and spent his childhood under the state’s apartheid-like Jim Crow laws (as seen in the recent horror series Lovecraft Country), which were only dismantled in 1955.

LaTanya: When I was a kid in Atlanta, Georgia, I was from a very awakened city and town because Martin Luther King and a lot of the civil rights movement was alive there. Growing up in that, the question of slavery and all that it entailed took on a form of me understanding that it was a crime rather than [slaves being] a race of people. I attached myself to the idea of the criminality of racism versus it really being about who I was descended from. I never quite was comfortable with saying I was the descendant of slaves, even though people said that a lot and we were told that a lot. But I couldn’t understand until later, as I grew older, why that wasn't sitting well with me. And it was because I kept saying, “But these people were not a race of people. It was not a religion. It was a crime. Slavery was crime.” To attach yourself to a prison and call yourself an inmate? I never got that. I worked at trying to create what I felt was more equitable and truer to what had occurred for me. And I have kept that my entire life.

Samuel: I had an oral history of slavery from my grandmother and my grandfather. My grandmother was born in the late 1800s, so her mother and her grandmother, who had raised her, were essentially people who had been slaves. She would talk about the things that they told her about. So I understood that life from another perspective. I had never thought of it the way LaTanya said – as a crime. When I was in the house with them, it was a way of life. I grew up under segregation so that [slavery] was a specific era when we were owned by people, and then we were not. But the attitudes that I had, I garnered from my grandmother and my mother from the oral history that they had and from what they were still doing in terms of working for the dominant culture. They were still trying to keep me safe from something that shouldn't have been a problem. I should have been able to walk around freely without worrying about offending a group of people that I didn't know. I lived around the corner from a particular place where people were lynched [the Walnut Street Bridge]. I was taught about that place. I was taught how to interact with the dominant culture in a certain kind of way because they didn't want those people to harm me, so that was my relationship with them.”

A personal journey

As difficult and painful as the history tackled in Enslaved is, it’s also an intensely satisfying series as Samuel takes his own journey back to Africa, to trace his roots to the Benga people of Gabon. The country granted Samuel citizenship and a Gabonese passport in August 2019 during filming.

Meeting the Benga people gave Samuel fresh insight into himself and his family back in the US. “To be in the middle of those people and move around and to be able to see what my family or my origins were and to understand, okay, this is why I like this, or this is why I don’t like those particular things – and to hear the history of their [the Bengas’] travels down North Africa to the beach to become beach dwelling people – it made me understand my love for the ocean and water and just being outdoors in the sun and experiencing that. It gives you a sense of belonging that is very different.”

“When I get to Africa, I always feel complete in a way. And this was an even greater sense of belonging, to a place that we talk about all the time. People say African American this, that and the other that's one thing, but to feel physically attached and know that you belong to this particular group of people… most Americans don't have that connection. Black Americans are almost treated like mongrels – yes, you're black, but we don’t know what you're attached to. And now I am attached to something.”

Watching Samuel meet the Benga people and explore his heritage is LaTanya’s absolute favourite part of their series. “It allowed me to be a part of someone's journey home,” she explains enthusiastically. “For me to be able to take that journey with him and know who he is, was a time of great emotional enlightenment for me. I tell him that there are instances where I could see who he is today, which relates to who his nation of people are in the Benga tribe. Because of their affinities, they are people of the sea and of the water, and that is totally in Sam's wheelhouse. This is who he is! He is a water person. There were just instances where I could pick up on as I watched him with those people, that I know are just totally Sam. So for me, it still is emotional when I even think about it. To know that he was able to do it. And yet I am still waiting to be able to do something like that.”

The trouble with history

The series gave LaTanya her own pleasures, too, in rewarding her fascination with history. “I love that part of it [Sam’s time in Ghana] being juxtaposed to diving for the ships, because I also love ships! Trying to see and trace the routes, it just all was a different part of the story that I kind of knew. And to see different other kinds of minutiae, the little things that were happening along the route. Little things that became big things that occurred, and how it was running parallel with Sam finding out who he was and where he came from. That's my favourite part. But I love the entire series because it's just something that's feeding my soul and it's something that we all need to grab hold of and learn from.”

Samuel adds, though, that they both had to make certain mental shifts while coming to grips with marine archaeology during Enslaved’s search for sunken slave ships with the Diving With A Purpose team. “When they presented the idea in the beginning that there were these ships that they could identify, in our theatrical and dramatic minds we thought of finding ships with fish going in there and shackles and skeletons,” Samuel admits. “You forget that the ocean moves and destroys stuff.” It’s why Enslaved’s meticulous tracing of shipping and financial records is such a vital part of the series. “The perpetrators of people perishing on that ship, who commissioned that ship, who insured it – all these different things lead you back towards what everybody always turns to: the saying of follow the money,” Sam notes. “We [African Americans] always think we're the only ones. But this series allows us to see that we're only a small part of this picture, it's way bigger than we had ever thought – the why and how, the business of it.”

Dismantling the legacy

While working on the series, Samuel and LaTanya saw the world around them unite to continue dismantling the legacy of the Transatlantic Slave Trade – all around the world. In June 2020, well before Enslaved premiered in the US [in October 2020], the statue of Bristol merchant Edward Colston, who made part of his fortune through the Transatlantic Slave Trade, was toppled and tossed into Bristol Harbour during a Black Lives Matter protest. “That was just serendipitous that it happened that way,” LaTanya laughs. “I remember the boys were telling us the story of how the statue was there and how heralded he had been basically because his family was so instrumental in building that town. But it was one of those serendipitous occurrences that just so happened to happen without our knowledge and it just played into it. It was like, wow! It had been a source of concern during the show that the statue was even there (it features significantly in episode 1). So much has worked together for the impact of what this documentary was trying to do.”

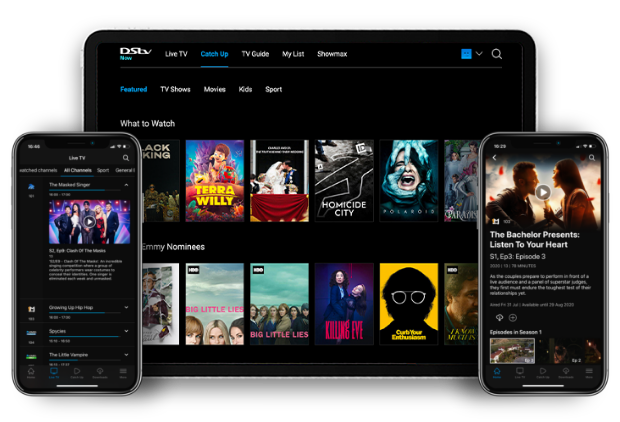

Enslaved S1 on Wednesdays on 1Magic (DStv 103) at 20:30 or on Catch Up. The series will later be available as a Box Set.